In recent weeks, a growing number of students across the country have set foot in their schools, some for the first time since last March. Here’s what they said it was like to return.

Maisie Robinson was so excited for her first day of kindergarten that she woke up at 2:30 a.m. to make her family breakfast.

“Unfortunately, the cereal was kind of soggy by the time we got up,” said her mother, Lindsey Post Robinson.

But that hardly dulled Maisie’s enthusiasm. She skipped to school last week in her purple coat, part of a wave of Chicago elementary school students who met their teachers and classmates in person for the first time.

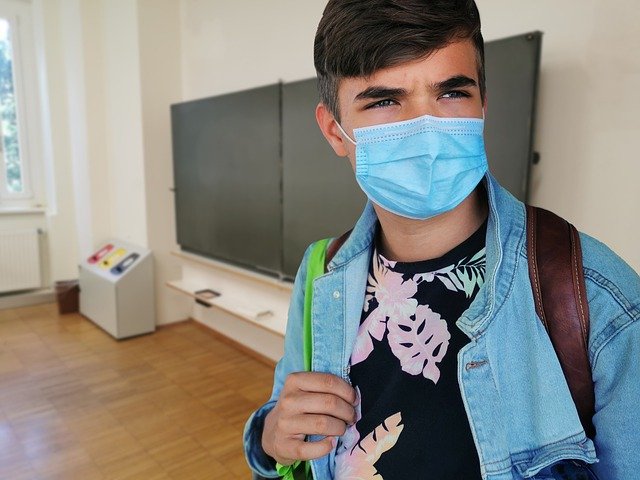

A year into the coronavirus pandemic, many American students have been in their classrooms since last fall — frequently off and on, as outbreaks have forced quarantines and closures. But in several large cities, students have started returning to school buildings only in the last few weeks.

The lower grades were the first to go back in much of the country, bolstered by research showing that young children are the least likely to spread the virus or to suffer severe consequences from Covid-19. Elementary and special-needs students led the way in Chicago, where a dispute between the city and its teachers’ union over school safety dragged out until February.

But gradually, a growing number of older students have been sliding back into their desks too. Chicago students in sixth through eighth grade began to return on Monday, although there is no plan yet for bringing back high school students, and most of the city’s families, at all grade levels, continue to choose remote learning.

New York City, the nation’s largest public school system, announced on Monday that it would welcome high school students back into classrooms starting on March 22, joining elementary school students, who came back in December, and middle schoolers, who returned late last month.

Many of those New York students spent a few weeks in classrooms last fall until a surge of cases forced them back onto laptops. The same was true in New Orleans, where after a weekslong purgatory of remote learning, high school students were recently able to once again walk their hallways.

“It was like a whole new beginning,” said Jzayla Sussmann, 18, a student at a charter high school in New Orleans. “I was so nervous, I didn’t sleep the night before.”

Many returning students — and their family members — shared that same anxiety and excitement as they waited for the alarm buzzer to announce their first day back. Here’s what some, from youngest to oldest, said it was like to return to the classroom.

CHICAGO

Sadie Santiago, 5

Frederick Stock Elementary School

As she left her preschool on Chicago’s North Side last week, Sadie Santiago was clutching a long rope with her classmates.

“That’s to ensure social distancing,” said her mother, Laura Santiago, watching them emerge. “They’re all six feet apart.”

Frederick Stock Elementary is an exception in the Chicago Public Schools: Although most classrooms remained largely empty last week, with a vast majority of families choosing to keep students at home, Sadie’s pod of 14 is nearly full.

Most of Stone’s students have special needs, some severe, her mother said.

“These kids need to be here,” said Ms. Santiago, a special education resource teacher at another Chicago school. Although Sadie does not have special needs, she suffers from severe asthma.

“I know so many people have been worried about these little ones wearing masks all day, but they have been fantastic,” her mother said. “These kids just want to play.”

Ms. Santiago said she believed that Sadie, who was attending a half day of school four days a week, was safe.

“I know the principal here, so I’m confident they’re constantly cleaning, wiping down toys and tables,” she said. “They’ve done so much to get them ready to come back.”

CHICAGO

Maisie Robinson, 6

Peterson Elementary School

The packing list for Maisie Robinson’s second day of school included some items you do not usually need for kindergarten: a laptop, which she has been learning on for months, and a plastic bag with three masks — one for the morning, one for after lunch, and one for gym class.

She carried them in a pink backpack alongside “Pancake” (which she named her lunchbox) for Friday’s four-block walk to school. On the way, she described how her classroom was arranged.

“There’s, like, a yoga mat, and everyone has a colorful circle, and we have tape around our area,” she said.

There is also plenty of space. Only eight of Maisie’s 24 classmates chose to return to in-person learning; she and three other students will be in class on Thursdays and Fridays, while the other four students will attend on Mondays and Tuesdays.

Sill, being in school is much better than learning from home on a computer, Maisie said.

“The fun thing about it is, the kids who are there in person get to find the word of the day during morning meeting,” she said. “I found the word Thursday, and then I had this fancy marker that I got to circle it with.”

Being deprived of social interaction has been difficult for an outgoing child like Maisie, said her mother, Lindsey Post Robinson, a marketing operations manager. Even now, things are nothing like normal school.

“When we got there yesterday she was all excited, but there was no one there,” Ms. Post Robinson said. “It was easy to get a parking spot, but it was so quiet.”

CHICAGO

Nathan Beaser, 9

South Loop Elementary School

The students in Nathan Beaser’s school are not allowed to socialize with one another at lunch, so for entertainment, the cafeteria staff puts on a television show. On Thursday, it was “Clifford the Big Red Dog.”

“I got to sit right in front of the projection screen,” said Nathan, who is in third grade, “so I could see best.”

Nathan said he was not sure about returning to school when his parents signed him up for in-person classes. “I was a little scared because I didn’t want to get the virus,” he said. “But I feel a lot better because of all the safety precautions. Like, just in case, we have tissues and hand sanitizer everywhere. And they take my temperature before I walk in and after lunch.”

Nathan’s parents are both physicians at the University of Chicago.

“I know the precautions that have been taken, and I know it’s safe,” said his mother, Anna Beaser. “I feel comfortable with the plan they have in place.”

NEW YORK

Aaron Levinson, 11

J.H.S. 157

Aaron Levinson, who has cerebral palsy, already considers himself a shy kid. Making friends is hard. And months of virtual learning to start off middle school made it harder, said his mother, Gwen Leifer.

Aaron attended a few days of in-person classes last semester before the citywide shutdown of public schools, but there were never more than two other classmates in the room, Ms. Leifer said. On some days, Aaron was the only student in class.

So it was to Aaron’s surprise and glee that when he returned to school in Queens last month, he found seven other students in the room — a result of his school combining cohorts. Now, he is finally making friends.

“I don’t want to be on remote anymore, but I’m going to have to on some days, like on Friday,” Aaron said. “And I’m really scared of school closing.”

After the first day back, Ms. Leifer said she got an “earful” about the new buddies Aaron had found. “Going back to school reassures him that some things are getting a bit more normal,” she said.

NEW YORK

Rebecca Rha, 13

M.S. 67

Returning to the classroom stirred up a mix of emotions for Rebecca Rha.

She had spent a few weeks in her Queens middle school in November, but when New York City’s entire school system closed because of rising virus cases, she settled into the routine of virtual learning: waking up late, staying in her pajamas, eating breakfast during class.

She missed her friends, yes, but the possibility of her school closing again dampened her enthusiasm. “I had low expectations,” Rebecca said.

Still, the chance to interact with her peers again was enough to get her in the building. And although school has not really felt like school — there is no hugging classmates, no passing notes, no side conversations — she is in the same classroom as her two closest friends.

“Even though we’re socially distanced, we’re next to each other, just six feet apart,” she said.

NEW YORK

Ray Francis, 13

M.S. 258

Ray Francis’s mother had planned to keep him in virtual school all year. They see his grandmother daily, and she was concerned about her health.

But it did not go well.

Ray’s grades dropped. He could not focus. Teachers could not help. His mother, Linda Mojica, said he was mentally “not there.”

So when his Manhattan middle school reopened, she made the decision to send him back. “It took until now, in the spring, for me to make the full commitment, understanding he needs to go back into the building, and that it’s OK for him to go back into the building,” she said.

It did not take long to notice a difference.

Ray said he is finishing his work more quickly. He can focus and retain information better. And it is easier to ask his teacher for help because his new in-person cohort includes fewer students than his online class.

“My grades are getting better,” Ray said. “I feel good. I want to learn. I feel happy about learning.”

After his first day back, Ray called his mother to tell her how it went. “He enjoyed it,” she said, adding that she had not heard him talk about school that way in a long time.

NEW ORLEANS

Freddie Sussmann, 15

Rooted School

As if ninth grade at a new school was not hard enough, Freddie Sussmann, whose family moved from Houston to New Orleans in August, has spent most of the year staring at black squares on his laptop screen, unable to meet his fellow freshmen, who usually keep their cameras off during remote learning.

Sometimes, he said, he is the only student who turns his camera on — but that just makes him feel more lonely.

“It’s like you’re trapped in a dark realm,” he said. “You can’t see anybody. It’s almost as if you’re being forced to not have friends or classmates to talk to.”

Although New Orleans allowed high schools to reopen for a hybrid mix of online and in-person instruction late last year, Freddie and his sister, Jzayla, were among the more than 80 percent of students at their charter school who opted to stay remote for the entire fall semester.

Around 40 percent have committed to in-person classes this semester, and when the building reopened last month, the siblings were some of the first to stream through the doors of the school, which is housed within one of the nation’s oldest synagogues.

“It’s like we’re in a church,” said an awe-struck Freddie, describing the bright classrooms and “cool” 3-D printers.

After four days in school, he made his first friend, a classmate who helped him with an algebra assignment. “I feel much better because it’s about time I had friends,” he said.

NEW ORLEANS

HiKing Joseph, 16

Lusher Charter School

On his first day back to school, HiKing Joseph was looking for the gym when he came upon some staff members and asked for directions. While showing him the way, one of the men introduced himself: he was the school principal.

Then he introduced HiKing to his teacher, who did not recognize the teenager even though they had spent months together in Zoom classes. “That was a surreal moment,” recalled the principal, Steve Corbett.

HiKing had attended school in person for one day last fall before deciding he would rather stay online. “He felt it was a big risk because he could just stay home and get the same thing that they’re doing in class,” said his mother, Ariana Joseph.

But as the fall progressed, they both realized that HiKing, who transferred during the pandemic to enroll in a special arts program, would benefit from hands-on instruction.

Since asking for directions on his first day back, HiKing has slowly begun to learn his way around the building. “It can be overwhelming at times,” he said.

He especially enjoys his art classes. While learning remotely, he completed assignments alone and submitted a photo of the project. But at school, he said, he gets to see how his classmates are progressing around him.

The social connections also extend to physical education, where he recently played a game of kickball. “You can’t do that at home by yourself,” he said.

NEW ORLEANS

Zoe Bell, 16

Ben Franklin High School

Zoe Bell could have returned to school in New Orleans last year, when public campuses first reopened. But she was worried about the health of her mother, who has lupus.

Most of her friends and many of her teachers chose to stay remote, so she did too.

The one exception was to play volleyball. A slew of safety measures, including temperature checks and limits on spectators, helped allay her concerns about playing sports during the pandemic.

By the end of the semester, however, Zoe was losing interest in remote learning. Most of her classmates kept their cameras off, and she was aching to see her friends in person again. But just as she was preparing to return in January, a winter surge in virus cases prompted school buildings across the city to close.

A few weeks later, Zoe, her mother and her sister fell ill with Covid-19, though they swiftly recovered. Once their 14-day isolation ended, she was looking forward to going to school twice a week — even if that meant having to wake up early again.

Late last month, Zoe sat in a classroom for the first time since last March. Many things were different. Before the pandemic hit, her largest class had 21 students. Now there are seven at most, their desks staggered to maintain social distance.

Students can eat lunch in the gym and under tents outside. Some of her classes are just study halls, rather than actual lessons.

But Zoe finds the sight of face masks to be the weirdest change. “It’s sort of surreal,” she said. “You’ll realize you’re in class with only a few people, and everyone is wearing masks. Sometimes I’m like, ‘Dang, when will we ever get back to normal?’”

NEW ORLEANS

Jzayla Sussmann, 18

Rooted School

The struggle of remote learning was real for Jzayla Sussmann long before the pandemic closed schools nationwide.

When Jzayla was in 10th grade, her mother decided to enroll her in an online home-school program before moving the entire family from New Orleans to Houston. There was no longer a school bus to wait for, classmates to hang out with or teachers to meet. A social butterfly, Jzayla watched with envy as her younger brother, Freddie, headed off to school in the mornings.

She was home-schooled for two years but decided to attend a traditional school for 12th grade. Then the pandemic hit, throwing her dreams of a normal senior year into doubt even after her family moved back to New Orleans in August.

When the high school she planned to attend stayed remote in the fall, Jzayla was crushed. “It hurt because I wanted to make friends,” she said.

On the day before classrooms reopened last month, Jzayla begged her mother to take her to the mall to buy a new outfit. She cleaned her room and got her book bag together in preparation.

Waiting for the school bus the first morning, Jzayla grew anxious each time another bus drove by. “I was like, ‘Oh, that’s our bus. That’s our bus, get ready,’” she recalled telling her brother.

Once they arrived, however, she was dismayed to find only three students in her classroom, and social distancing made it hard to break the ice. “I didn’t know if I knew how to make friends anymore,” she said.

Still, she said, just being around other students makes her happy. And having her teachers nearby gave her a fresh boost of confidence. “I felt motivated, like I wanted to do more,” she said. “I haven’t felt that way in a while, and I got a lot of work done.”